I have never been one to take the earth seriously. It is troublesome to do so. I feared what it might demand; I feared how immersed I might become. It might make me a different person. It might put me out of my comfort zone. I didn’t like that. It was inconvenient and I was comfortable in the convenience of my laziness. There was also scepticism. Is the earth really dying?

Then, I started writing this story. A story that made me think a bit more about environmentalism and climate change. Before this, before now, the only time I had given some attention to the earth was a year-and-a-half ago, when I was preparing for my English language test to come to the UK. I assumed I was going to be tested on various issues. And so, I had learnt the basics: carbon footprints, green house emission, fossil fuels and the likes.

But this goes beyond that. This story begins at a university in the south of England. I am in Dorset, living just an hour away from the historic Jurassic Coast. As part of our journalism coursework, I have been assigned to explore the privilege of living by this coastline, and the luxury of taking care of my new environment. I read up on the history of the landscape, the fight of the people to protect their environment, the choices that some people make every day to keep the earth alive. I listen to the stories of the environmentalists. And I find myself on a journey to find the environmentalist in me. But before I tell you about that, let me take you on a journey to sub-Saharan Africa.

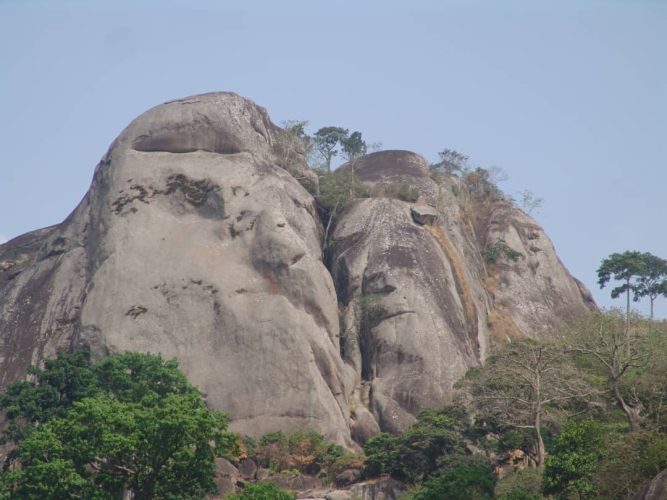

It is 2008, I am seven. I am in the back seat with my siblings, on a family trip. In our black Xterra jeep, we are driving along an unpaved, bumpy road, a family of six. My parents point to a batholith. My siblings and I look up excitedly. It is fierce, intense, simply powerful.

Where is home to you?

Nigeria. A populous nation with diverse cultures and languages. To talk about all the cultures and dialects of the many languages in Nigeria is like trying to swallow a handful of eba all at once. I am from southwestern Nigeria, the part of the country known for skilled craftsmanship. We are known for infusing everything that we cook with spicy pepper. My ethnic group is Yoruba, and almost like the spiralling wrap of a croissant, with just so many rolls, there are so many dialects of the Yoruba language. My family is from Ondo, which has a population of about 723, 823. Most of southwestern Nigeria’s landscape are plains, valleys and plateaus. One of the major tourist attractions in this state is the popular Oke Idanre (Idanre Hills), a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

We arrive at Oke Idanre. There is something thrilling about the first sight of this intimidatingly huge hill. I am not thinking much of this site, or how it relates to the earth at this point. I am simply excited about the adventure of climbing to the top. So is the rest of my family. And so, we begin climbing.

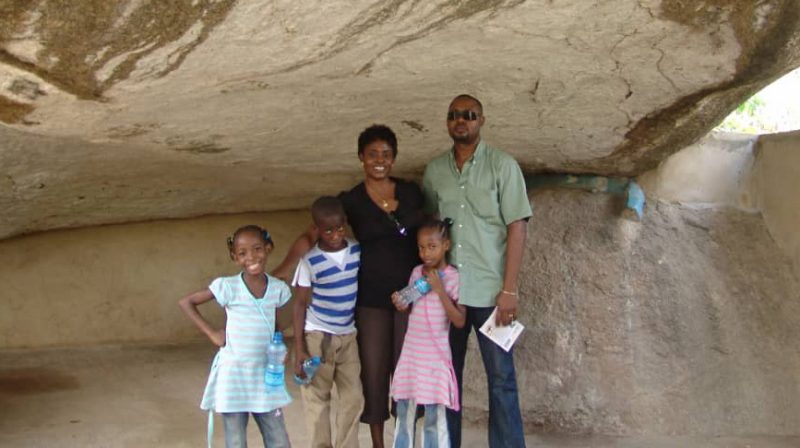

The hill is on high plains, overlooking stunning valleys. It is 3,000 feet above sea level, located on an igneous batholith, which is about 500 million years old. Reaching the top involves climbing 682 steps. You have the opportunity of resting in five places. Our whole family make it to the top (proof in the images above and below); we kids now have something exciting to write about for our holiday schoolwork.

These hills tell stories of ancient times. The founder of Idanre is believed to be Aremitan, the brother of Oduduwa, who founded the Yoruba land. After Oduduwa’s death, there followed a bloody conflict. Aremitan and his followers fled to these caves. Today, the Idanre town lies at the foothills. Famous attractions here include the Owa’s Palace (King’s Palace), the shrine, and the Omi Aopara (Thunder Water). The place is home to the unique Perret’s toad (Amietophrynus perreti), and other species such as the hyrax, which sadly are being hunted into extinction by the inhabitants.

My house in Lagos is a six-minute walk from a lagoon, which is connected to the much-bigger Lekki Lagoon. I remember standing by the water some 10 years ago, looking at floating plastic and waste, and wondering: has it always been like this?

Nigeria, ranking among the highest producers of plastic waste globally, has very few policies implemented to protect green space. The effects of climate change, specifically at heritage sites like Oke Idanre, will lead to damaging consequences such as riverbank erosion, flooding, and river toxicity. There have been actions from people such as Alex Akhigbe who, in partnership with the Africa Cleanup Initiative, made it possible for pupils in a school in Ajegunle to pay their tuition fees with used plastic bottles. Dagunduro Ade, an artist, also thought outside of the box, using waste materials to create art. But there seems to be a long list of actions the government must implement for a greener Nigeria to exist. One of which is to enact into law the bill prohibiting the use of plastic bags.

There is also a need for unconventional thinking and creativity. A study by Usaman Awan, published in the Journal of Cleaner Production, highlights the role of creativity in improving sustainability performance and engendering green innovations. If this is adopted in Nigeria, alongside implementing the right policies and creating opportunities that promote a sustainable lifestyle, a greener Nigeria just might come into view.

But it isn’t that littering is always the case in Nigeria. There is the story of petty traders recycling plastic bottles. There’s the unintended sustainable practice of such traders going through garbage, walking the streets in search of plastic bottles thrown out of vehicles. These bottles are cleaned, and used to bottle palm oil, kerosene, zobo and other produces.

There is also the story of families — including mine — reusing plastic bottles and plates as opposed to throwing them away because they see that as a waste. I mean, it is pretty common in a Nigerian home to find an ice-cream container in the freezer containing anything else but ice-cream.

Looking back at it now, there are stories of Nigerians who have always lived and still practice a sustainable lifestyle — not in a bid to protect the earth, but simply to cut down on their cost of labour or living.

But still, all of that did not make me a climate change enthusiast. It was just something I did, but did not think too much about. An environmentalist is someone who is concerned about the state of the earth. Was I concerned? Or just aware of dangers from climate change? Did I contribute seriously to sustainability? Yes, I do the basic stuff of recycling my waste. Although, sometimes, I ponder about what I do. The other day, I was in front of the trash bins, tearing the packaging from some caramel slices. I got sick of the whole recycling culture, having to make a decision, especially as I was unsure if the packaging was recyclable or not. In this, I am not alone. An article in Forbes shows that while the percentage of Americans wanting to recycle is high, only 35 per cent of them actually end up recycling because they do not know how to recycle or what can be recycled.

The steps at Lulworth are steep.

The Jurassic Coast, in the south of England, runs through Devon and Dorset. Spanning 95 miles, it is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Famous landmarks of the Jurassic Coast such as the Lulworth Cove, the Stairway Hole, Durdle Door all point to history, what it once was — a span of desert during the Mesozoic era. Over millions of years, the landscape has changed. It was a desert during the Triassic era, during the Jurassic era; it was a tropical sea, and a wetland during the Cretaceous age. Now, it is a beautiful coastline.

If parts of my country ever had a changing landscape like this coast, I am eager to find out. The Lulworth Cove was formed when a crack within the Portland stone formation led to the erosion of sea water. Rocks around the cove such as the Portland Stone, Purbeck Beds, Wealden Clay, the Greensand and the Chalk date back millions of years ago. Lulworth’s erosion from the waves have made it larger and larger.

I have arrived at the cove on a sunny afternoon on the X54 Jurassic Coaster from Bournemouth. Hopping off at the bus stop, standing on what was once a desert millions of years ago, I am thrilled. I walk through the car park, towards the flight of stairs cut into the hill that would take me from the Lulworth side to Durdle Door, I begin my adventure. I look up, dreading the steep climb.

The steps were steep, cut into a wide green hill — the kind Maria Rainer might hike up and eventually run and run on in The Sound of Music. The view is breathtaking; the beauty of the green land that spans acres, slowly merging into rock hills. As I climb, panting like I had completed a 100m race, what lies below starts to appear even tinier. The rock hill covered in green grass, which nests a white, castle-like house somewhere to the left of the steps, look like a dash of white paint on green.

I continue climbing. Reaching the top, I savour the stunning view. The sea is way below, glistening in the setting sun. There is a calmness in the slow and sure movement of the waters below. I see it all, yet not completely. How wide the sea is! Again I feel overwhelmed. I think now of how well this heritage site is taken care of, compared to Oke Idanre.

But with the climate constantly changing, will the Lulworth Cove stand the test of time? How the landscape has changed, and how it would change further in the coming 300 million years is something to think about. Possibly these beautiful landmarks won’t exist anymore in the future. And that would be a pity.

It is a little after 7:00pm. I sit on the X54 Jurassic Coaster, top deck, front row, watching the view in real time, one last time. The cottages and grasslands speed past. I try desperately to imprint everything on my mind, to miss not one thing. I close my eyes to the beautiful landscape of Lulworth Cove.

Writing this story was a journey. From ideation to seeing for myself what the coast entails, reflecting on my childhood trip to Oke Idanre, thinking, screening my actions when recycling, wondering, judging my concern for the earth, reflecting on the habits of my people towards climate change, all of it was a new experience. New, because it is the beginning of my awakening, of seeing climate change with new eyes.

And yes, there has been a change. I can say now that I have awakened a little more to these issues. This journey has allowed me to reflect on the wrong choices that I had mindlessly been making about my environment, the importance of protecting heritage sites back in my country and in my new environment. If the careless decisions we make lead to the destruction of historical landmarks like these, it would be a crime. Storms, flooding, loss of heritage all can be avoided if we become a little concerned about the state of the earth and take consistent actions together.

But I am also overwhelmed. No, I am exhausted. I am searching for a bigger climate activist in me, but I haven’t found that person yet. I am swamped by the information I have consumed, by the challenges to save the earth. Everyone is talking about it. I mean, the baby wipes on top of my makeup box has an inscription that reads: Plastic free & plant-based wipes. It is like everyone needs to tell everyone else about what they are doing for sustainability. Why did the local politician feel the need to talk about how vegan his biscuit was just the other day? And there’s me, just wanting to eat meat.

The plastic bags I use for my dustbin is changed every time I empty the trash bin. And I know that’s a problem too. If I get serious, if I processed things a little more deeply, I could be guilt-tripped into reusing the bags. I think there are some actions we take just to avoid the guilt we may otherwise feel. And so, these ‘sustainable actions’ that we take aren’t quite sincere; it’s somewhat selfish. Does that matter? What matters is that we are making a change, right?

Emily Johnston in her article on Loving a Vanishing World writes: We can feel fear and grief and anger, in other words — we can even feel avoidant sometimes — and still attend to the world’s very real and immediate needs, as long as we don’t let our feelings be an excuse for abandoning our responsibilities. This honest reflection calls to light the headspace of my emotions, and the humanity of allowing myself to feel these emotions. But there is also the will to fight against these emotions that might leave me, leave us, complacent. We should act and serve the earth in hopes of saving it little by little, as opposed to letting our emotions control our actions, and be the reason why we do nothing. I should look beyond my fear of change. I should go beyond that, and show up. Showing up and doing a little better than what I did before or doing something new, something I never have done before despite my anxiety for change.

I think everything that has happened up until this point in my life has somehow forced me to be here, to be part of a story like this. I may never have given ears to the dying earth if I never had to write a story on climate change. If I never had to travel to Lulworth and write a story on the Jurassic Coast, I’d still be the same — unchanged, indifferent. I feel as though I have been removed from my previous reality and thrust into this chaotic state of living that calls on me to help change the earth. I am learning to never feel it is too late to show up. That is where I am at.